Finding Triumph in Tragedy

by David Chrisinger

“Weep, darling. Weep…and then, tomorrow, we shall make something strong of this sorrow.”–Lorraine Hansberry, “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window”

When he was discharged from the Marine Corps in 2006, Mike Liguori knew he had changed. “My reactions to the violence of Iraq coupled with multiple near death experiences caused an immense amount of pain in my life,” he wrote. “In 2007, I was diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress (PTS). I remember when the doctors told me of their findings; it felt like a death sentence.”

Liguori was told that post-traumatic stress was incurable and that the only way he could manage the symptoms was through the use of antidepressants and talk therapy.

“I didn’t like the way the pills made me feel,” Liguori continues, “and couldn’t get past my therapist never experiencing combat. Everything she said to me about my experiences went in one ear and out the other.”

After he stopped going to counseling and stopped taking his medications, Liguori says that his post-traumatic stress made his daily life almost unbearable. He even considered taking his own life.

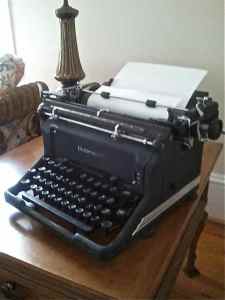

Then, when he was at his lowest, Liguori started writing about his experiences.

“The moment I typed those first words on the keyboard, uncensored thoughts and memories from Iraq poured out. My first entry turned into 10 pages of flashbacks and memories that were subconsciously hidden in the depths of my mind.”

“I felt unbelievable,” Liguori continues, “to have the weight of PTS that had held me down since I left the military finally start to feel lighter…. When I decided to share my experience with others, I found my friends and families’ reactions to be insightful and powerful. It was the first time I felt connected to other people by sharing my stories.”

As human beings, we have always related to one another by telling and listening to stories about ourselves and others. We have, in turn, always understood who and what we are — as well as what we might become — from the stories we tell each other.

Those who buy in to the theory of Narrative Identity argue that identity is not a single, fixed core self that we can “reveal if we peel away the layers.” Instead, each and every one of us constructs our own identities — conceptions of who we believe ourselves to be — primarily through the integration of life experiences into an internalized, evolving, and communicable story.

According to Donald Polkinghorne, “We are in the middle of our stories and cannot be sure how they will end; we are constantly having to revise the plot as new events are added to our lives. Self, then, is not a static thing or a substance, but a configuring of personal events into a historical unity which includes not only what one has been but also anticipations of what one will be.”

These stories — life stories, if you will — provide us with both a sense of unity and purpose if we tell them the right way.

Indeed, those who are able, the theorists continue, to incorporate negative or traumatic life events into their life stories as instances of redemption tend to be happier than those who do not. In a redemptive story, the narrator transitions from a generally bad or negative state to a generally good or positive state. Such a transition is characterized as:

- sacrifice (enduring the bad to get to the good),

- recovery (attaining a positive state after losing it temporarily)

- growth (bad experiences actually bettering the self), or

- learning (gaining or mastering skills, knowledge, and/or wisdom in the face of the bad).

Incorporating your experiences into a redemptive life story allows you to organize memories and more abstract knowledge into a coherent biographical narrative. In other words, turning your disparate experiences into a coherent story helps you to construct, organize, and attribute meaning to your experiences, as well as to form, inform, and re-form your sources of knowledge and your view of reality.

Travis Switalski, an Army infantry veteran with multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, turned to writing as a way to cope, and found it to have a transformative effect on his memories.

“Writing about my experiences in the military,” he writes, “has given me more in the way of recovery than medication or therapy ever had. Putting down on paper what happened to me and those around me has helped me to understand the trauma that we were subjected to, and to help let go of some of the guilt that I was holding on to personally.”

“There is something liberating,” he continues, “about getting all of that mental mess out of my head and heart and putting it into an organized, understandable thought that others can read and comprehend. Translating it for them has helped me understand it better myself.”

In this sense, crafting a life story that makes sense of our lack of coherence with both ourselves and the chaos of life is a tremendous source of growth and transformation.

This May, at the 2nd national Military Experience & the Arts Symposium, it will be your turn to say what you need to say, to turn your trauma into triumph. Joseph Stanfill and I will be leading a workshop in which we will help you tell your stories of redemption and post-traumatic growth. If you have a story to tell, please consider joining us in Lawton, Oklahoma.

So I wasn’t surprised when Doc began sending me links to videos from the wars. On occasion some of us indulge ourselves in the imagery and sounds of combat. We scratch that itch in a way that’s masochistic, nostalgic, and indicative of the bizarre allure of adrenaline. Modern technology has created an internet that is awash with footage of combat. We can take our pick between an Apache strike, a machine gun’s hammering rattle, or a stream of tracers racing across those all-too-familiar cityscapes. Anyone can. Many do. We wouldn’t be the first generation to revisit these things. In The Great War and Modern Memory, Paul Fussel told us about World War One veterans of Great Britain purchasing phonograph records of the sounds of artillery bombardments on the Western Front.

So I wasn’t surprised when Doc began sending me links to videos from the wars. On occasion some of us indulge ourselves in the imagery and sounds of combat. We scratch that itch in a way that’s masochistic, nostalgic, and indicative of the bizarre allure of adrenaline. Modern technology has created an internet that is awash with footage of combat. We can take our pick between an Apache strike, a machine gun’s hammering rattle, or a stream of tracers racing across those all-too-familiar cityscapes. Anyone can. Many do. We wouldn’t be the first generation to revisit these things. In The Great War and Modern Memory, Paul Fussel told us about World War One veterans of Great Britain purchasing phonograph records of the sounds of artillery bombardments on the Western Front.