Review: Ellouise Schoettler’s “Arlington National Cemetery: My Forever Home”

By Roger Thompson, Stony Brook University

See Ellouise Schoettler’s Arlington National Cemetery: My Forever Home here. Start a discussion with Roger and others who’ve viewed the performance below.

Two years ago, I visited my father-in-law at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio. He had been buried in 1997, two months before I married his daughter, and since that time, neither I nor my wife had returned. For my wife, a visit was too complicated. The difficulties of family dynamics had, in his death, left her under a shadow whose boundaries she had yet to trace, and the fact that he had not made known to any of his family, even his own wife, that he had made plans to be buried alone in the military cemetery caused confusion and even anger. I did not share that family history, and though his secret decision seemed to me hurtful, it also seemed to me full of some meaning that needed to be honored, and at some point, understood. My trip to his grave was an attempt to help my wife try to tell her father’s story and choice of final resting place again, perhaps in a new way. It was also a way for me to try to, more than ten years after his death, reconnect with the person who would have been my father-in-law had cancer not claimed him in his fifties.

Connection is at the heart of Ellouise Schoettler’s story-telling, and I get the sense, watching her Arlington National Cemetery: My Forever Home that her visits to the resting place of both one of her daughters and her husband at Arlington National Cemetery is more than just, as she says at the end of her performance, “remembrance” of the dead. Her performance derives from the finest traditions of story-telling, and it is about animating the lives of the dead so that the living connect with them, understand them, and recognize them as neighbors breathing life into us like the first spring air that breaks winter. That Schoettler concludes her nearly hour-long rumination on death without so much as mentioning the word “death” is testament to the fact that she’s actually more interested in life, or that, more accurately, she is interested in collapsing the line between life and death in order to make it so thin that marking out its boundaries is like trying to distinguish one brilliant white marble headstone from among all the others in their perfect rows. Step in close, you will see the firmly etched name of an individual. Look up and cast your eyes around, and you will see only the collapsing certainty of the white rows.

Schoettler’s story-telling is complex. While it leans on a sentimentalism like that from Keillor’s mythical Lake Wobegon, it doesn’t rest in that place. Instead, it complicates such sentimentality by the use of remarkable juxtaposition. Her narrative opens with the burial of one of her children nearly fifty years ago, and that story is the force that moves her toward the burial of her husband in 2012 after more than fifty years of marriage. As her story moves onward, she punctuates the family remembrance with stories of her future “neighbors,” those who are buried next to her husband, her child, and one day her. These are reminisces of death, beautifully told, and in each case, focused not on the loss, but on the breathing, loving, and continuing lives of those left behind. Arlington is transformed in these narratives, then, into a community that bustles with energy. It is no less lonely than any other cemetery (the image of survivors sitting next to their loved ones’ headstones repeats in her tales), but, unlike other stories of loss and loneliness, there is in Schoetller’s Arlington the certainty (not merely possibility) of reunion, connection, resolution, and perhaps even peace.

The most striking of the juxtapositions gestures toward this certainty. Schoettler is driving into Arlington on one of her many trips to see her husband, and as she drives toward the grave, she is overrun by a mass of twelve year old children. They are on a field trip, and they roll toward her like a wave up the road. She pulls over to let them pass, and as they do, she engages one of their teachers in conversation. They are here on a field trip, having driven in from New Jersey, and after seeing the tomb of the Unknown Soldier, they are making their way to lay a wreath at the grave of an alumnus of the school who had been recently killed in Afghanistan. The children, of course, are full of life, darting along, laughing, running, enjoying a warm day out and away from school, and yet, despite their clatter, they are “beautiful” to Schoettler, their sounds pressing life into the sacred space. They are also the exact opposite of the dignified procession of her husband’s burial related earlier in her narrative, and while she makes no comparison explicit on this point, it is impossible in listening to her relate the story of the field trip, not to have in one’s mind the contrasting images of the flag-draped carriage drawn by Marines down the road and the bubbling mass of children swarming up it. One image focuses on ritual and silence, the other on buzzing and blissful chaos. Maybe more, it is also impossible for me not to hear in that story the recovered voice of her own daughter, chattering above the earth. She begins the performance with the death of her child, and as her narrative weaves its way to a conclusion, the mass of children arrive, crowding her out, pushing her to the side to make way for their almost impossible joy in summer. Her loss, then, is new life not only for herself and her family, but for her child, who lives now in her listeners, and she essentially erases the line that separates us from the dead. We hear them as well as the children. We hear her as well as her child and husband. We hear the story of parents, children, warriors, and civilians as they spin out from Schoettler’s tales, and we are ultimately witness to their enduring parade.

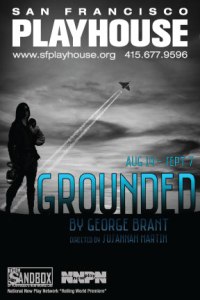

This fall, Susannah Martin directed George Brant’s play Grounded at the

This fall, Susannah Martin directed George Brant’s play Grounded at the

Dominic is continuing to work as a practicing artist. Since the Arts and the Military/AMH week he has created murals in Chicago and in Santa Barbara — the first for the National Veterans Art Museum and the second for the University of California at Santa Barbara.

Dominic is continuing to work as a practicing artist. Since the Arts and the Military/AMH week he has created murals in Chicago and in Santa Barbara — the first for the National Veterans Art Museum and the second for the University of California at Santa Barbara.